Our last day on the road began like most of our days, under clear blue skies. Whizzing down the 20-kilometer hill from Khandala I thought how lucky we've been throughout this entire trip. Excellent weather with hardly any rain. A helpful tailwind most days (today being no exception). And best of all, practically zero technical problems or accidents. Despite constant togetherness Fred and I have gotten along tremendously well, and we've encountered precious few assholes along the way. Of course no day is perfect --where would be the fun in that?\-- and today's big worry was once again the traffic. The Pune-Bombay road is probably one of the busiest in India.

We had to slalom our way around the much slower-moving trucks, but it was a fun descent regardless. At the bottom of the hill we paused at a phone stand to try (unsuccessfully) to call our parents and to get information on the road ahead. We had a choice to make regarding the route and after much deliberation decided to stick with the main road as far as Panval, still forty kilometers off. It wasn't so bad, thanks to a generous shoulder and the continuing tailwind. Once we turned off towards Uran, however, the wind was no longer with us and I noticed suddenly that I felt like crap: feverish and entirely lacking in energy.

The newish road took us over some desert-y ridges before dumping us onto a vast, ugly marsh. Each push of the pedal took a lot of effort and concentration on my part. When we finally reached Uran I collapsed onto a chair thoughtfully provided by a concerned shopkeeper and guzzled down a couple of liters of water. The port town of Mora was still a few kilometers off, and I cringed at the thought of having to climb back into the saddle. But the road to Mora wasn't bad at all, even beautiful, snaking up and down under shady trees, through traditional villages and finally to the funky little port.

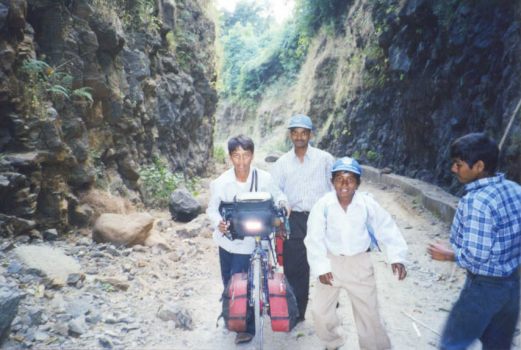

The dismal road to Uran

We learned that a ferry to Bombay was leaving immediately and raced to the end of the long jetty. The boat was full but we managed to squeeze our bikes and ourselves on board before the pokey little vessel chugged slowly off towards the Bombay skyline. A female passenger informed me that we wouldn't be landing at the Gateway to India as I had thought, but rather at a ferry terminal some miles away. This came as a disappointment, not only because the Gateway to India was right next to where we intended to stay, but also because I liked the symbolism of it.

During the long, hot voyage I could think of little besides crawling into bed and passing out. I told Fred how I had had a dream the other night that this very boat would sink, dragging our bikes down to the bottom of Bombay harbor. With the boat listing radically towards the port side, it wasn't inconceivable that my dream was prophetic, but we somehow made it, and were soon pushing our steeds through the melee that awaited us at the other end. The ride to Colaba was pretty intense, though by no means our worst riding in India. The whole port district was jammed with transport modes of every conceivable ilk and the streets were a solid waiting mass.

We wormed our way through most of the knots, but occasionally had to wait in the exhaust for a hole to appear. Much of our route was lined with slum housing, constructed out of found materials right on the sidewalk. Apparently if you occupy the same spot for three years the government recognizes it as yours. When I stopped to take a photo of this Bombay phenomenon swarms of kids came running towards me, no doubt thinking of pens. I made a narrow escape and soon we were in familiar --and relatively calm---Colaba. When we arrived at the doorstep of our hotel Fred and I looked at each other incredulously.

Slow (and scary) boat to Bombay

Was this it? Were we done riding? Had we actually made it? We gave each other a big hug and felt flooded with all kinds of weird emotions. Once upstairs I scrubbed off the dirt of our last riding day and flopped onto the bed, feeling utterly spent. My first impressions of Bombay when we passed through on our way to Jalgaon were sub-optimum. Walking and riding through town I felt I would expire form the chokingly bad air, become deaf from the noise, go mad of claustrophobia due to the crowds and broke because of the expense. Arriving the second time I had a different impression.

To some degree I credit my re-evaluation of the town to the simultaneous euphoria and disappointment of the trip's imminent end. My new appreciation of the town was only marred by Andy's bad disposition inspired by his ill health. This time we'd chosen to stay in Colaba, a district favored by tourists. Close to the harbor and the towering Taj Hotel, Colaba offered conveniences I was unaccustomed to. Cafés, Internet services, shops with western goods, occidental faces and a multitude of other opportunities presented themselves. One of Bombay's offerings is the only queer bar in India. A little larger than the average closet but smokier and darker, its primary advantage was that it was just a few hundred meters from our hotel.

Curiously, despite its proximity I only managed to visit once. There we met Captain Sean, whom I assumed must be in the armed services with his title. His short-cropped hair, square jaw, strong frame and jovial disposition did little to refute that assertion. He was literally twice the size of any other patron in the bar and was the dominating presence there. Sean had downed a few and was doing his best to bring us all down with him by being very liberal with his bar tab. Sean teetered noticeably as the night went on. Still recovering from dysentery, I had to refuse Sean's generosity and was consequently less jovial than my compatriots.

Imminent urchin attack in Bombay's sidewalk slums

As everyone was further on his journey to drunkenness than me I began to find the conversation less and less compelling. I shuffled off early though goaded to make some Indian friends by everyone around me. One boy vying for my friendship was a beanpole of a boy showing more midriff than Madonna. He jiggled wildly to every tune western and eastern making his intentions known to the entire bar. In spite of his enthusiasm I said my good-byes and walked out alone. Before I even reached the door beanpole-boy was on to the next customer. Our conversations revealed that Sean worked not for the navy or air force but for a shipping company.

He lived in Dubai and was on assignment in India. One of the perks of his job was a car and driver whom he generously loaned to us the next day. We went on a jewelry shopping junket with the driver before joining Sean for lunch. He invited us to the Mexican (yes, Mexican) restaurant in his hotel. I was ready for very bad food. I remembered vividly what horrible facsimiles of this cuisine I'd sampled in so many other countries the last two years. The watery and sugary margaritas were a bad sign. When our shortish, dark and heavily accented waitress arrived at the table I assumed she was Indian.

After a few words I recognized her accent as Mexican. Andy, the waitress and I conversed a little in bad Spanish only to find out that she and eight other Mexicans ran the restaurant. The food was authentic. At lunch we learned the details of Sean's dual life: By day -- a sea captain working for a large shipping company acting straight and living in fear that he might be discovered as a homo; fearing dismissal if his sexuality is revealed he is relegated to talking about females, sex, girlfriends and conquests. By night and weekend -- a wildly out and open gay man.

Ashok at the Humsafar Center

We had the chance to see both in action. It was funny to see him so at ease talking to his driver about his wife and mistresses and then at work at a gay venue that night. Our friend, a gay activist in Bombay, Ashok, had agreed to take us out to a "real" Indian gay venue, King's Circle Park. Aptly renamed "Queen's Circle" was crowded when we arrived. As its name implies the circle lies in the center of a busy roundabout. Pathways crisscross the park and run around the exterior fence. Indian families and their kids populate one half of the park while the remainder is the turf of Bombay's gays.

The two groups share the wide walkway that bisects the park. I renamed the path "the line of actual control" after the dividing line between India and Pakistan. Within minutes of entering the park and walking the line Sean met someone and disappeared. Andy and I were both shocked with the alacrity with which Sean adapted to Indian homo culture. Andy and I hung out with Ashok and his friends. They work (literally, unlike Sean) the park, distributing condoms and teaching park-boys about AIDS and how to avoid it. Ashok shared with us his alarming assumptions about the rate of infection in India.

It was great to see Ashok in his element. At one point the ugliest and oldest guy in the park came up to Andy and me, introducing himself to Andy with obvious interest. In an unbelievably generous and graceful display Andy quickly excused himself, leaving me with the perving goon. It took me five minutes to loosen myself from his grip, barely escaping a nasty demise. Later Sean rejoined us sans his new friend who had escaped to run an errand. Our time at the park had passed quickly and the park began to close. The guards bearing large sticks politely asked everyone to leave and the crowd dispersed to the annex in an orderly fashion.

Captain Sean

On the traffic island we agreed to go for a drink with Ashok and his friends. Just as we were leaving for the bar Sean's friend reappeared with a belated birthday card for Sean. Are they destined for marriage? After drinks Sean, Andy and I retreated to have dinner at the Italian restaurant at his hotel. But as we left Andy's ugly and creepy suitor from the park was laying in wait for us outside. This time he'd set his sights on Sean. "I am a businessman, you come to my house for sex," was his order. We indicated that it was our intention to do something else and he retorted "I have a taxi and will drive you."

Sean saw the contradiction between this statement and the last and dismissed him when he made his final appeal, "you give me money." The best part of our stay in Bombay were our interactions with native Indians in their homes. Ashok was especially instrumental in organizing our social calendar including a lunch at his home in Santa Cruz (a suburb of Bombay). It was the first time in ages I truly felt relaxed. Ashok's mom dazzled us with culinary specialties of the south from her home in Goa. We retired to their modest living room where Ashok stretched out on the floor to soothe his aching back.

From the floor he told us of his dramatic life as an activist amidst the objections to his posture by his mother. I asked him why there were thick protective bars on the door, "Is it dangerous in Santa Cruz?," I asked. "No, but they are to protect my mother and I from the Hindu extremists. They have attacked me and my mother several times." It was then I realized what the commitment he'd made in becoming a gay activist. Ashok and his mother are literally in physical danger for their outspokenness on a daily basis. Another of Ashok's social events was dinner with the "movers and shakers"

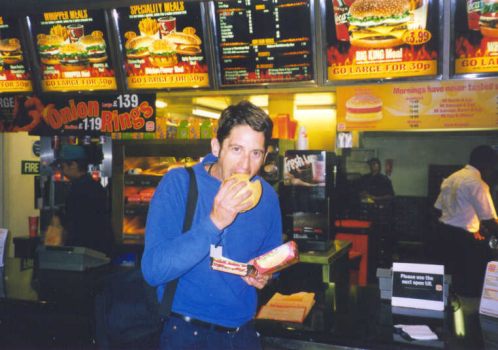

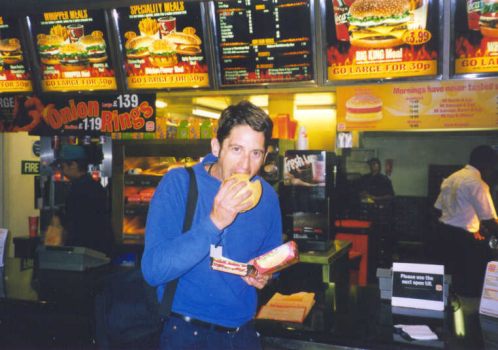

One sacred cowburger to go, please

of gay Bombay in a penthouse apartment overlooking the sea. Half the adventure was getting there on the unfathomably crowded suburban trains. Every surface of my body was pressed against another, rendering it unnecessary to hold on as the car bumped and jolted. Fortunately we were taller than most of the others on the car so I could see above the heads of our fellow travelers; otherwise I'd have surely gotten claustrophobia. At the dinner guests ranged from executives of computer companies to a costume designer from Bollywood. When the costume designer arrived in a Roman gown and golden sandals I was speechless.

I wondered if we should bow and shout "Hail Caesar" upon his entry. In contrast to this dinner on the set of Anthony and Cleopatra was one held at the house of Shelly and Noshir whom we met in Dungarpur. They proved to be even more charming and gracious than they were on the road. Noshir insisted on picking us up in Colaba and driving us out to their frightfully tasteful apartment on Malabar Hill. Sipping scotch and exchanging travel stories we entertained one another well into night before returning to Colaba. No visit to Bombay would be complete without a trip to the movies.

We chose the Bollywood super-hit "Bombay Boys" for our outing. Arriving at the ticket office we were disappointed to find that the first tickets available were two weeks after our departure from India. Before the corners of our mouths had a chance to droop we were being escorted to a side street where scalpers had tickets for today's performance for only 100% more than face value (still less than a dollar each). It was hard to concentrate on the film with all the activity in the theater. Conversations, cell-phone calls, beepers beeping, people jeering and singing along with the songs were all part of the landscape in the theater.

Olivier and Stephane

It was a good thing that we were distracted by the social aspects of going to the theater because the film itself was nothing to get excited about. When it was finally time to leave Bombay I was thankful for the distraction of the logistic of moving our bikes and gear to the airport. Those details kept me from having to ponder the emptiness I felt from having to leave India and end our trip. Our last taxi fare drama felt anticlimactic. It seemed like it might be simpler just to pay the thieving driver thrice the fair fare as he demanded.

That would harm the next unsuspecting tourist so we argued one last time over a taxi fare, unloaded our gear and headed home. Our itinerary read like a shopping bag from Gucci: London-Paris-New York. Yet the glamour of it failed to inspire any thrill in either of us. Were we ready to re-immerse ourselves in the developed world? Arriving in London had the expected surreal quality. Heathrow looked so orderly, empty and clean. And so many white people. We had no idea how to get our bikes into town (or whether to entrust them to the left luggage people) and explored the options.

In the end we took the new bike-friendly express train to Paddington Station, walking distance to where we'd be staying. It cost ten pounds a person, which seemed princely sum after months of bickering over pennies, but the luxury and speed were worth it. Whisked through the Londonian gray I thought back on the decrepit, overcrowded commuter trains we'd taken in Bombay and smiled. Once arrived at the station we locked up our bikes and stopped at Burger King for our first taste of beef in months, which came as a bit of a disappointment, actually. Lucky for us the weather outside wasn't too cold, balmy even.

Spinning in Tucson -- not quite the same...

But London seemed deserted, a ghost town. By coincidence our friends Olivier and Stephane from Paris were also staying at the Mulhern residence while they (the Mulherns, that is) were skiing in Switzerland. Since it was New Year's Eve they had a whole agenda planned for us, culminating in a very French-flavored dinner party in Soho. The main course wasn't served until after midnight, at which point I could only think of bed and escaping from the new Cher song that our hosts played incessantly. Was I ready for the so-called real world? To this weary traveler, moneyed, staid London seemed a lot less real than anywhere we'd been in India.

The next morning I joined Olivier on the first Eurostar train of the year. He managed to sleep the whole way to Paris while I gazed disorientedly out the window, even through the chunnel. Paris was far easier to digest since I was on familiar ground and surrounded by all the friends I'd accumulated over the eight years I lived there, along with a couple of new ones. The ten days I spent there went by as a delightful, hedonistic blur. Angela and her two daughters made me a dinner worthy of Thanksgiving; we shopped for winter coats and shoes; and a couple of days were so warm that Fred and I were able to eat lunch on café terraces.

I could have stayed for another month, but didn't want to overstay our welcome chez Olivier et Stephane. After a quick stop back in London to see Max, Myriem and their kids (freshly arrived from the Alps) we were back in the air on our way to New York --the most uncivilized city on Earth? After only one night spent at my sister's place, Fred and I parted ways, he to California on the deathflight (*Tower Air emergency landing after losing an engine and hydraulics in a 747*) from hell and I to Boston on creaky old Amtrak. It felt funny traveling on my own again.

Now we're reunited here in Tucson, where we've spent the last six weeks working on this website and making new friends. This town has to rank as one of the most welcoming, laid-back places anywhere. The weather here is superlative, the people are uncomplicated and unpretentious and the bizarre scenery makes for exquisite hiking and biking. It'll be hard to leave, especially when neither of us knows yet where we'll end up calling home. Has this experience changed our lives? I imagine it has, though I think we're both still pretty much the same people as when we left almost exactly two years ago.

On the other hand, it's definitely changed the way I look at the world. The most jarring thing I've noticed lately is how materially-oriented we Americans tend to be, identifying ourselves through the objects we possess and dreaming about how to acquire new ones. Traveling under our own power and limited to what we could carry on our bikes was ultimately a very liberating experience. Most of our own possessions are still lying in storage in Watsonville, California, and I, for one, have no burning desire to be reunited with them, as they'll most likely re-complicate my life. Another appreciable difference is how confident I feel.

Having braved the unknown (and often scary) roads of Asia and survived to tell about it, I feel capable of achieving practically anything --just not sure what that thing is yet...