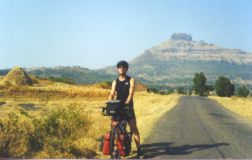

| 24 December, Ahmednagar to Pune, 122km (a)

It was the best of roads, it was the worst of roads. Since arriving in Maharashtra Fred and I have been very impressed with this state’s highways: well-surfaced, well-graded and well-maintained. Today’s road was no exception, though it did have an overabundance of the only negative element of Maharashtran roads –namely, Maharashtran drivers.

The first part of the ride was actually all right. After escaping Ahmednagar’s dusty honking sprawl we found ourselves traversing a hilly Californoid landscape, rolling up and down various ghats and valleys. The traffic was busy but by no means unendurable, making the kilometers click off at a fairly brisk pace.

At the top of the day’s second hill lay the daddy of all dhabas, the fanciest highway rest stop in India, if not all of Asia, a gleaming mirage promising snacks and rest called –bewilderingly— "The Smile Stone." While Fred munched on his customary 10 a.m. ice cream I visited the toilets, which for me rivaled the Taj Mahal in terms of grandeur and impact. The place was immaculate, full of sparkling marble and obsequious attendants dressed in crisp white linen. I should have taken a photo.

The rest of the day was pretty unremarkable. On the outskirts of a place called Shirur we had lunch and talked with the place’s owner, who told us another foreign cyclist had been by earlier, also on his way to Pune. Shirur was more or less our day’s half-way point, and marked the place where the traffic turned from bad to worse. Strangely, the road grew narrower as the traffic volume increased, forcing us to dive off onto the soft or non-existent shoulder more times than I care to remember. Maharastrans drive faster than their Rajasthani and Gujarati counterparts, and the state’s relative wealth translates into a far greater number of vehicles. Where were they all coming from?

Next stop was the crossroads town of Shikrapur. I had had enough of the traffic; over a dosa snack I proposed to Fred that we charter one of the many waiting vehicles, but my idea was rejected summarily. "It’s only another 45 kilometers. At the rate we’re going we’ll be there in two hours," argued my still-energetic riding partner. While I agreed with him in principle, always preferring to do things the pure way, I also value my life and wondered if I could take any more of the scary driving.

It actually got scarier, and the anticipated two hours turned out to be longer due to the frequency with which we were run off the road. The traffic was practically solid all the way into Pune, though this didn’t seem to stop drivers from attempting suicidal passes. I had to stop a few times just to remind myself to breathe. I refrained from resorting to my usual tactic of projecting my brain into a more serene space; the road required my full attention. By the time we reached the town’s outskirts we had to abandon the road entirely and ride on the bumpy dirt shoulder that ran alongside it, dodging people, animals and lawnmower-taxis all the while.

We crossed a bridge into the heart of Pune, and took the first left on the other side. It was like entering another world. After a full day of choking on dust with our ears ringing of motorsounds, we were suddenly swallowed into a leafy and quiet residential district. It looked vaguely like an upmarket neighborhood in any American city, with trendy little cafes, elegant housing and –could it be true?—a Baskin Robbins shop, scooping up no fewer than 31 flavors. We could scarcely believe our eyes, sitting down immediately for a serious ice cream pig out. All this time we’d been praising Gujarati ice cream, but really there’s no comparison. It was like what a prisoner must go through when he tastes gourmet food for the first time after years in the joint. While experiencing this ecstasy we met a young Canadian woman who spends six months a year in Pune, taking yoga and reiki classes and basking in the place’s New Age energy. Her association with the nearby (and infamous) Osho ashram was unclear. "No, I’m not a member, but I like to go there to hang out," she said mysteriously.

Baskin Robbins shares an outdoor terrace with a large caf� catering almost exclusively to Westerners, most of whom were wearing maroon-colored robes and all of whom were in poseur overdrive mode. One customer was very ostentatiously reading something by Emmanuel Kant while others sat cross-legged with their eyes closed. It reminded me of Caf� Pergolesi back in Santa Cruz, only more ridiculous –partly due to the silly costumes, but mostly because we were, after all, in India, thousands of miles from Europe and America.

Our Canadian friend told us that there were all sorts of Christmas parties going on tonight and recommended a couple of hotels. One was right above the caf�, but it was full, as was the one across the street and a couple more around the corner. Never having encountered such problems in India, we began to wonder if Pune was fully booked, but finally found a room in a groovy old deco place right next door to the Osho ashram.

Osho is the current moniker of a guru who used to go by the name Rajneesh back when he was operating out of Oregon and driving around in his many Rolls Royces. Remember? He got nabbed on tax evasion and fled the country, back to his native Pune to set up this place. While he’s no longer "in the body" (i.e. dead), the cult is still going strong and seems to attract mostly Europeans now. Lots of French and Germans running around in maroon robes, screwing each other with wild abandon (freedom of sexuality is a big part of the Osho schtick, and, presumably, its draw). After washing off seventeen layers of caked-on road dirt, we went for a sunset stroll. On the way over to the ashram we passed a young woman holding a rose up to her nose and wearing the most bogus beatific expression I’ve ever seen. I can’t recall a time I’ve felt a stronger urge to punch someone in the nose. Others, all clad in maroon, came streaming out of the ashram’s elegant gates, looking similarly brainwashed. We tried to get inside for a peek but this was strictly verboten. How did our Canadian friend get inside if she wasn’t a member? And if we two BikeBrats found these people so transparently phony, what on earth did they think of the likes of us? Here we were, surrounded by people of our own race and backgrounds for the first time in months, yet never had we felt so alien, so other.

We continued our stroll, past a strip of street stalls selling maroon garments, including underwear, plus the usual assorted subcontinental kitsch. We stopped at an extremely popular Western-style (right down to the prices) caf� for espressos, surrounded by still more poseurs and feeling self-consciously out-of-the-loop. What the hell was this place all about, I wondered only half-curiously, knowing that we’d never find out since we plan to hit the road again bright and early tomorrow morning. The Internet "caf�" we stumbled upon surprised us by having the best prices and connection we’d found anywhere in India, and the Italian restaurant we dined at afterwards (recommended by our Canadian friend) was superbly tasty. Back at Baskin Robbins we hung around half-hoping we’d get invited to a Christmas party, realizing at the same time that our energy level would make us total party duds. Besides, who would want to invite freaks like us? We weren’t even wearing maroon.

So we headed back to our squeaky-clean hotel room, where this (unabridged and unexpurgated) article in the local newspaper caught my eye:

Pune District Records Highest Road Mishaps

Solapur: The Maharashtra State Road Accidents Control Committee member Chandmal Parmar today disclosed that Pune district recorded highest number of road accident in the country due to the increasing population and increase in vehicles.

Talking to press persons here, Parmar said that during last 40 years, Pune’s population has increased four folds.

The roads length and width have been made 5 time whereas the vehicles have been increased 90 times of the previous strength which have broken all times accident records.

Giving details about the road mishaps, Parmar said that in the country there were 36 vehicles behind 1000 people.

In Maharashtra the number was 50 and in Mumbai it was 150 but in Pune there were 350 vehicles behind a thousand people.

"Out of the total 49.46 lakh vehicles in the state, Pune has 9.95 lakh vehicles while Mumbai is still behind with 8.95 lakh vehicles," he said.

Parmar said that to suggest measures against road accidents the committee travelled three thousand kilometre and visited 2500 accident spots so far.

The state government has allocated Rs. 12 crore to minimise road accidents he added.

While it’s refreshing to have our suspicions on the local drivers confirmed, it’s a wonder we survived today’s ride. For tomorrow I’ve got a more rural route planned in order to avoid the surely nightmarish road from here to Bombay. I’m hoping getting out of Pune will be less of a hassle than getting in.

|

Yabba-Dhaba-Doo: The Smile Stone

Any color you like, as long as it's maroon

|

Xmas at the loony bin: spaghetti anyone?

On the road to Khandala

Indian roadside assistance

|

25 December, Pune to Khandala, 87km (f)

An alarm clock is a superfluous investment if you live within a few hundred yards from the Osho Ashram in Pune as we did. Well before the crack of dawn the animalish noises began. They invaded my dreams before rousing me to consciousness. Visions of Tarzan swinging through the trees, bestial sexual acts and fights between feral cats were inspired by the wild hooting next door. I made an effort to sleep through their screams in the darkness in vain, finally just lying in bed staring at the ceiling trying to guess what they were actually doing over there.

Finally we walked to breakfast at the poser caf� where tourists and ashram visitors munch baked goods chased down by espresso and cappuccino donning their western-hipsters-in-India outfits. Buzzing from my first coffee in ages we packed our bags and headed for our last stop on the road to Bombay. On the way out of town we stopped at the gate of Osho’s place to photograph some of the comers and goers. A rather rough looking goon sprinted up to us and threateningly said "No photos Bapu, this is private property". As far as I could tell we were on the street in the middle of the town and not on anyone’s land. Not being easily menaced by such behavior, in fact taking it more as a challenge, I asked if he was intending to hurt us. I continued by asking if that was in keeping with Osho’s teachings while Andy happily snapped away. Osho’s bouncer’s bark was worse than his bite and he backed-off at the instruction of his keeper, a gray-bearded, white-frocked Osho follower.

Under the scrutiny of all the Oshos we pedaled down the street and out of Pune towards the hill station where we’d celebrate Christmas. I’d have forgotten entirely the significance of the day had it not been for the invitations to parties the night before. We’d managed to ignore it and it looked liked we’d make it through this day without any reminders. No wreaths, xmas carols, gift-giving, trees, football games, eggnog, fruitcake or any other traditions would appear this day, at least until much later. We were a little lost on our way out of town. We had to stop often to ask directions because our maps were insufficient. Finally, as we became completely frustrated looking for the right turn-off a man on a scooter stopped to help us find our way. After hearing our destination and story he said "You just go to Paud, turn right and after seven kilometers stop in at my place for some tea."

We did just that, but not before stopping at a little roadside restaurant for some food. Seven kilometers down a valley over a bumpy road along side hills covered with golden brown grass we reached a rather large house. Several folks seemed to be clumsily engaged with a construction project in the yard, and when they saw us they stopped their work, opened the gate and beckoned us in. This must be the place. When the workers summoned the lady of the house she seemed confused and a little perturbed by our presence. I thought we’d made a mistake and was ready to leave when her tone suddenly and inexplicably changed. We were invited in.

They led us to the second floor where twelve folks were finishing their xmas dinner which was composed of spaghetti, which they were slurping up from their hands. They were eating western food in honor of the holiday and their visitors from the US and Germany. "Do you want some?" they asked. "No thanks," we’d just eaten and the idea of pasta without a fork and spoon wasn’t that interesting. Then they told us what was going on. This was a center for the rehabilitation of differently-abled folks. The German guy and girl from the US were volunteers. A group photo had to be taken and tea had to be drunk. We shared the story of our journey and excused ourselves to recommence our journey.

The journey became more intense after our little stop. Steep ascents and descents dogged us as we circumnavigated a massive reservoir. We met more characters including some fishermen who were wading in a small lake with neither nets nor poles, leaving us wondering if they were catching prey with their teeth or hands.

The end of the day had the all-too-familiar "when will this day ever end" feel to it. Each climb seemed steeper as the sun dipped precariously close to the horizon. Finally the road turned directly up the side of the ridge away from the lake and towards the town we both assumed was our destination. The last kilometer the road ceased to be paved and steepened. The grade was so severe that the gravel and rocks couldn’t bear to hold traction for our wheels. Just before our path deteriorated we’d passed thirty catcalling adolescents out for a day hike. I loathed the idea of them catching up with us and pushed more rapidly than Andy. They caught up with him and laughed at him for pushing the bike. In response he indignantly invited them to try to get the bike up the hill. They too were relegated to pushing it, soon caught up with me and pushed mine up as well. After but a few hundred meters they too were nearly exhausted and tried to return the bikes to us. We refused, insisting they finish the job.

At the top another barrier was reached. The unstable walls of the road cut at the ridge were crumbling and huge rocks were falling twenty meters from the top of the ridge onto the road along with tons of dirt and gravel. The kids tried to tell us that malicious monkeys were tumbling the debris onto the road. It seemed unlikely unless the monkeys were trained to operate heavy equipment and set explosives. In actuality there was a road crew working to stabilize the road cut and they’d just blasted some debris. We couldn’t see the work, but we could see a man with a hard hat on the other side of the cut making a hand motion for us to stop and wait out the rock fall. After a few minutes he motioned for us to proceed. I took my bike back from the boys as did Andy and we hauled our bikes one hundred meters over fresh dirt and rocks as fast as we could for fear the fall of more on our heads. We all made it through safely though out of breath and ready for the day to finally end.

The route down to town was even bumpier than the way up. At least traction wasn’t an issue so we bounced down through the busy hill station in search of lodging. Not having any idea how to find our hotel we asked a cop who proved himself, like most cops in India we’d met in India, to be worthless. A bystander who noticed our confusion and frustration offered to let us follow him on his motorcycle to the road and in the direction of the "elegant" resort that would be home for the night. Too sleepy and hungry to shop for an alternative we ended up in a room that had a fantastic view of gorge that perforated the ghat. Our overpriced lodgings included a Christmas buffet, entertainment and breakfast. Indulgence of my hunger was something I felt I owed myself after one of the tougher riding days of the last two years. We ordered room service, stuffing down dosas and pakora.

I wish we’d avoided the buffet altogether. Poolside tables had been set and a warm wind blew up the ridge from Bombay below. The food was nasty and the entertainment even worse. A "family-fun" weekend had been promised to guests and the hotel was delivering. A kids karaoke contest was staged during the meal. We were subjected to insufferable audio torture while we ate cold curry under the stars. Is this a holiday?

Waking in Khandala (f)

I can’t believe it is almost over. I feel like a child at the very end of his school holidays. Should I rejoice at the idea of re-entering "normal" society or cry for having to give up this marvelous adventure? Further scrambling my emotions were two emails received recently. One warned me that I’d received a certified letter from the IRS and another informed me of an offer to interview for a marketing position back in the states. Am I ready for the day-to-day complications and comforts of a life at home? Makes me wish I had the financial independence to go on riding without concern for money. Do I have the temperament or resolve to make that happen?

Now the sun is filling the deep gorge below my balcony and I begin to ponder more immediate concerns. What will our last day look like? I know (or, rather, hope) that it will end in Bombay, how exactly it is up to the gods, a little luck and our ingenuity. We know that there is a boat from the mainland that can take us to Bombay letting us avoid the morass of traffic that floods the streets of the city. We are unsure about when it operates and from where. We also know that we are on top of a massive hill and will to ride to sea level. Some part of the day should allow us to feel the rush of the wind through our hair and hear the whir of our gears and tires.

Now it is time to put aside the mundane thoughts of my future and the trivial concerns of logistics and enjoy this day, the last riding day of our trip.

|

| 26 December, Khandala to Bombay, 81km (a)

Our last day on the road began like most of our days, under clear blue skies. Whizzing down the 20-kilometer hill from Khandala I thought how lucky we’ve been throughout this entire trip. Excellent weather with hardly any rain. A helpful tailwind most days (today being no exception). And best of all, practically zero technical problems or accidents. Despite constant togetherness Fred and I have gotten along tremendously well, and we’ve encountered precious few assholes along the way. Of course no day is perfect –where would be the fun in that?-- and today’s big worry was once again the traffic.

The Pune-Bombay road is probably one of the busiest in India. We had to slalom our way around the much slower-moving trucks, but it was a fun descent regardless. At the bottom of the hill we paused at a phone stand to try (unsuccessfully) to call our parents and to get information on the road ahead. We had a choice to make regarding the route and after much deliberation decided to stick with the main road as far as Panval, still forty kilometers off.

It wasn’t so bad, thanks to a generous shoulder and the continuing tailwind. Once we turned off towards Uran, however, the wind was no longer with us and I noticed suddenly that I felt like crap: feverish and entirely lacking in energy. The newish road took us over some desert-y ridges before dumping us onto a vast, ugly marsh. Each push of the pedal took a lot of effort and concentration on my part. When we finally reached Uran I collapsed onto a chair thoughtfully provided by a concerned shopkeeper and guzzled down a couple of liters of water. The port town of Mora was still a few kilometers off, and I cringed at the thought of having to climb back into the saddle. But the road to Mora wasn’t bad at all, even beautiful, snaking up and down under shady trees, through traditional villages and finally to the funky little port.

We learned that a ferry to Bombay was leaving immediately and raced to the end of the long jetty. The boat was full but we managed to squeeze our bikes and ourselves on board before the pokey little vessel chugged slowly off towards the Bombay skyline. A female passenger informed me that we wouldn’t be landing at the Gateway to India as I had thought, but rather at a ferry terminal some miles away. This came as a disappointment, not only because the Gateway to India was right next to where we intended to stay, but also because I liked the symbolism of it. During the long, hot voyage I could think of little besides crawling into bed and passing out. I told Fred how I had had a dream the other night that this very boat would sink, dragging our bikes down to the bottom of Bombay harbor. With the boat listing radically towards the port side, it wasn’t inconceivable that my dream was prophetic, but we somehow made it, and were soon pushing our steeds through the melee that awaited us at the other end.

The ride to Colaba was pretty intense, though by no means our worst riding in India. The whole port district was jammed with transport modes of every conceivable ilk and the streets were a solid waiting mass. We wormed our way through most of the knots, but occasionally had to wait in the exhaust for a hole to appear. Much of our route was lined with slum housing, constructed out of found materials right on the sidewalk. Apparently if you occupy the same spot for three years the government recognizes it as yours. When I stopped to take a photo of this Bombay phenomenon swarms of kids came running towards me, no doubt thinking of pens. I made a narrow escape and soon we were in familiar –and relatively calm—Colaba.

When we arrived at the doorstep of our hotel Fred and I looked at each other incredulously. Was this it? Were we done riding? Had we actually made it? We gave each other a big hug and felt flooded with all kinds of weird emotions. Once upstairs I scrubbed off the dirt of our last riding day and flopped onto the bed, feeling utterly spent.

|

The dismal road to Uran

Slow (and scary) boat to Bombay

Imminent urchin attack in Bombay's sidewalk slums

|

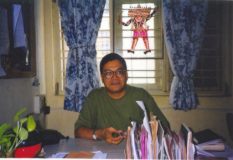

Ashok at the Humsafar Center

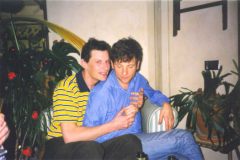

Captain Sean

|

26-30 December, Bombay (f)

My first impressions of Bombay when we passed through on our way to Jalgaon were sub-optimum. Walking and riding through town I felt I would expire form the chokingly bad air, become deaf from the noise, go mad of claustrophobia due to the crowds and broke because of the expense. Arriving the second time I had a different impression. To some degree I credit my re-evaluation of the town to the simultaneous euphoria and disappointment of the trip’s imminent end. My new appreciation of the town was only marred by Andy’s bad disposition inspired by his ill health. This time we’d chosen to stay in Colaba, a district favored by tourists. Close to the harbor and the towering Taj Hotel, Colaba offered conveniences I was unaccustomed to. Caf�s, Internet services, shops with western goods, occidental faces and a multitude of other opportunities presented themselves.

One of Bombay’s offerings is the only queer bar in India. A little larger than the average closet but smokier and darker, its primary advantage was that it was just a few hundred meters from our hotel. Curiously, despite its proximity I only managed to visit once. There we met Captain Sean, whom I assumed must be in the armed services with his title. His short-cropped hair, square jaw, strong frame and jovial disposition did little to refute that assertion. He was literally twice the size of any other patron in the bar and was the dominating presence there. Sean had downed a few and was doing his best to bring us all down with him by being very liberal with his bar tab. Sean teetered noticeably as the night went on. Still recovering from dysentery, I had to refuse Sean’s generosity and was consequently less jovial than my compatriots. As everyone was further on his journey to drunkenness than me I began to find the conversation less and less compelling. I shuffled off early though goaded to make some Indian friends by everyone around me. One boy vying for my friendship was a beanpole of a boy showing more midriff than Madonna. He jiggled wildly to every tune western and eastern making his intentions known to the entire bar. In spite of his enthusiasm I said my good-byes and walked out alone. Before I even reached the door beanpole-boy was on to the next customer.

Our conversations revealed that Sean worked not for the navy or air force but for a shipping company. He lived in Dubai and was on assignment in India. One of the perks of his job was a car and driver whom he generously loaned to us the next day. We went on a jewelry shopping junket with the driver before joining Sean for lunch. He invited us to the Mexican (yes, Mexican) restaurant in his hotel. I was ready for very bad food. I remembered vividly what horrible facsimiles of this cuisine I’d sampled in so many other countries the last two years. The watery and sugary margaritas were a bad sign. When our shortish, dark and heavily accented waitress arrived at the table I assumed she was Indian. After a few words I recognized her accent as Mexican. Andy, the waitress and I conversed a little in bad Spanish only to find out that she and eight other Mexicans ran the restaurant. The food was authentic.

At lunch we learned the details of Sean’s dual life: By day – a sea captain working for a large shipping company acting straight and living in fear that he might be discovered as a homo; fearing dismissal if his sexuality is revealed he is relegated to talking about females, sex, girlfriends and conquests. By night and weekend – a wildly out and open gay man. We had the chance to see both in action. It was funny to see him so at ease talking to his driver about his wife and mistresses and then at work at a gay venue that night. Our friend, a gay activist in Bombay, Ashok, had agreed to take us out to a "real" Indian gay venue, King’s Circle Park.

Aptly renamed "Queen’s Circle" was crowded when we arrived. As its name implies the circle lies in the center of a busy roundabout. Pathways crisscross the park and run around the exterior fence. Indian families and their kids populate one half of the park while the remainder is the turf of Bombay’s gays. The two groups share the wide walkway that bisects the park. I renamed the path "the line of actual control" after the dividing line between India and Pakistan. Within minutes of entering the park and walking the line Sean met someone and disappeared. Andy and I were both shocked with the alacrity with which Sean adapted to Indian homo culture. Andy and I hung out with Ashok and his friends. They work (literally, unlike Sean) the park, distributing condoms and teaching park-boys about AIDS and how to avoid it. Ashok shared with us his alarming assumptions about the rate of infection in India. It was great to see Ashok in his element.

At one point the ugliest and oldest guy in the park came up to Andy and me, introducing himself to Andy with obvious interest. In an unbelievably generous and graceful display Andy quickly excused himself, leaving me with the perving goon. It took me five minutes to loosen myself from his grip, barely escaping a nasty demise.

Later Sean rejoined us sans his new friend who had escaped to run an errand. Our time at the park had passed quickly and the park began to close. The guards bearing large sticks politely asked everyone to leave and the crowd dispersed to the annex in an orderly fashion. On the traffic island we agreed to go for a drink with Ashok and his friends. Just as we were leaving for the bar Sean’s friend reappeared with a belated birthday card for Sean. Are they destined for marriage?

After drinks Sean, Andy and I retreated to have dinner at the Italian restaurant at his hotel. But as we left Andy’s ugly and creepy suitor from the park was laying in wait for us outside. This time he’d set his sights on Sean. "I am a businessman, you come to my house for sex," was his order. We indicated that it was our intention to do something else and he retorted "I have a taxi and will drive you." Sean saw the contradiction between this statement and the last and dismissed him when he made his final appeal, "you give me money."

The best part of our stay in Bombay were our interactions with native Indians in their homes. Ashok was especially instrumental in organizing our social calendar including a lunch at his home in Santa Cruz (a suburb of Bombay). It was the first time in ages I truly felt relaxed. Ashok’s mom dazzled us with culinary specialties of the south from her home in Goa. We retired to their modest living room where Ashok stretched out on the floor to soothe his aching back. From the floor he told us of his dramatic life as an activist amidst the objections to his posture by his mother. I asked him why there were thick protective bars on the door, "Is it dangerous in Santa Cruz?," I asked. "No, but they are to protect my mother and I from the Hindu extremists. They have attacked me and my mother several times." It was then I realized what the commitment he’d made in becoming a gay activist. Ashok and his mother are literally in physical danger for their outspokenness on a daily basis.

Another of Ashok’s social events was dinner with the "movers and shakers" of gay Bombay in a penthouse apartment overlooking the sea. Half the adventure was getting there on the unfathomably crowded suburban trains. Every surface of my body was pressed against another, rendering it unnecessary to hold on as the car bumped and jolted. Fortunately we were taller than most of the others on the car so I could see above the heads of our fellow travelers; otherwise I’d have surely gotten claustrophobia. At the dinner guests ranged from executives of computer companies to a costume designer from Bollywood. When the costume designer arrived in a Roman gown and golden sandals I was speechless. I wondered if we should bow and shout "Hail Caesar" upon his entry.

In contrast to this dinner on the set of Anthony and Cleopatra was one held at the house of Shelly and Noshir whom we met in Dungarpur. They proved to be even more charming and gracious than they were on the road. Noshir insisted on picking us up in Colaba and driving us out to their frightfully tasteful apartment on Malabar Hill. Sipping scotch and exchanging travel stories we entertained one another well into night before returning to Colaba.

No visit to Bombay would be complete without a trip to the movies. We chose the Bollywood super-hit "Bombay Boys" for our outing. Arriving at the ticket office we were disappointed to find that the first tickets available were two weeks after our departure from India. Before the corners of our mouths had a chance to droop we were being escorted to a side street where scalpers had tickets for today’s performance for only 100% more than face value (still less than a dollar each). It was hard to concentrate on the film with all the activity in the theater. Conversations, cell-phone calls, beepers beeping, people jeering and singing along with the songs were all part of the landscape in the theater. It was a good thing that we were distracted by the social aspects of going to the theater because the film itself was nothing to get excited about.

When it was finally time to leave Bombay I was thankful for the distraction of the logistic of moving our bikes and gear to the airport. Those details kept me from having to ponder the emptiness I felt from having to leave India and end our trip. Our last taxi fare drama felt anticlimactic. It seemed like it might be simpler just to pay the thieving driver thrice the fair fare as he demanded. That would harm the next unsuspecting tourist so we argued one last time over a taxi fare, unloaded our gear and headed home.

|

| Epilogue (a)

Our itinerary read like a shopping bag from Gucci: London-Paris-New York. Yet the glamour of it failed to inspire any thrill in either of us. Were we ready to re-immerse ourselves in the developed world?

Arriving in London had the expected surreal quality. Heathrow looked so orderly, empty and clean. And so many white people. We had no idea how to get our bikes into town (or whether to entrust them to the left luggage people) and explored the options. In the end we took the new bike-friendly express train to Paddington Station, walking distance to where we’d be staying. It cost ten pounds a person, which seemed princely sum after months of bickering over pennies, but the luxury and speed were worth it. Whisked through the Londonian gray I thought back on the decrepit, overcrowded commuter trains we’d taken in Bombay and smiled.

Once arrived at the station we locked up our bikes and stopped at Burger King for our first taste of beef in months, which came as a bit of a disappointment, actually. Lucky for us the weather outside wasn’t too cold, balmy even. But London seemed deserted, a ghost town. By coincidence our friends Olivier and Stephane from Paris were also staying at the Mulhern residence while they (the Mulherns, that is) were skiing in Switzerland. Since it was New Year’s Eve they had a whole agenda planned for us, culminating in a very French-flavored dinner party in Soho. The main course wasn’t served until after midnight, at which point I could only think of bed and escaping from the new Cher song that our hosts played incessantly. Was I ready for the so-called real world? To this weary traveler, moneyed, staid London seemed a lot less real than anywhere we’d been in India.

The next morning I joined Olivier on the first Eurostar train of the year. He managed to sleep the whole way to Paris while I gazed disorientedly out the window, even through the chunnel. Paris was far easier to digest since I was on familiar ground and surrounded by all the friends I’d accumulated over the eight years I lived there, along with a couple of new ones. The ten days I spent there went by as a delightful, hedonistic blur. Angela and her two daughters made me a dinner worthy of Thanksgiving; we shopped for winter coats and shoes; and a couple of days were so warm that Fred and I were able to eat lunch on caf� terraces. I could have stayed for another month, but didn’t want to overstay our welcome chez Olivier et Stephane.

After a quick stop back in London to see Max, Myriem and their kids (freshly arrived from the Alps) we were back in the air on our way to New York –the most uncivilized city on Earth? After only one night spent at my sister’s place, Fred and I parted ways, he to California on the deathflight (Tower Air emergency landing after losing an engine and hydraulics in a 747) from hell and I to Boston on creaky old Amtrak. It felt funny traveling on my own again.

Now we’re reunited here in Tucson, where we’ve spent the last six weeks working on this website and making new friends. This town has to rank as one of the most welcoming, laid-back places anywhere. The weather here is superlative, the people are uncomplicated and unpretentious and the bizarre scenery makes for exquisite hiking and biking. It’ll be hard to leave, especially when neither of us knows yet where we’ll end up calling home.

Has this experience changed our lives? I imagine it has, though I think we’re both still pretty much the same people as when we left almost exactly two years ago. On the other hand, it’s definitely changed the way I look at the world. The most jarring thing I’ve noticed lately is how materially-oriented we Americans tend to be, identifying ourselves through the objects we possess and dreaming about how to acquire new ones. Traveling under our own power and limited to what we could carry on our bikes was ultimately a very liberating experience. Most of our own possessions are still lying in storage in Watsonville, California, and I, for one, have no burning desire to be reunited with them, as they’ll most likely re-complicate my life. Another appreciable difference is how confident I feel. Having braved the unknown (and often scary) roads of Asia and survived to tell about it, I feel capable of achieving practically anything –just not sure what that thing is yet…

|

One sacred cowburger to go, please

Olivier and Stephane

Spinning in Tucson -- not quite the same...

|